Book Introductions

Explore each biblical book with our engaging introductions. To dive deeper, join the community for weekly lessons.

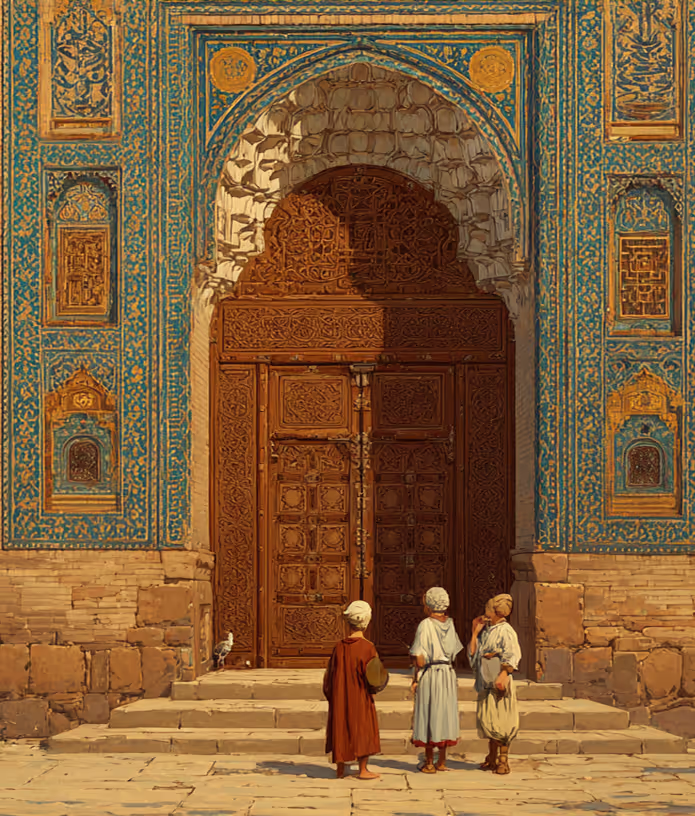

Old Testament

The Old Testament has been studied and analyzed for thousands of years. Even archeological finds, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, confirm not only written scrolls of the biblical text, but textual commentaries dating back centuries before Christ...but understanding the Old Testament requires investigating cultures far removed from our own and examining challenging belief systems and practices. Ancient Near Eastern and African cultures feature prominently in the Old Testament, as the people of God experience both triumph and tragedy, clinging to eternal promises even in exile. Three primary sections comprise the Old Testament: The Law, The Prophets, and The Historical Books. Filled with complex symbolism and seemingly strange cultural practices, as well as overwhelming violence in the Old Testament can make us hesitant to dive in, but the New Testament cannot be fully understood without the Old. The last prophetic word of the Old Testament marks the beginning of a four-hundred-year stretch of silence, only broken by John the Baptist in the New Testament, inextricably linking the two and giving us a glimpse of a God who is omnipresent.

Jeremiah

Jeremiah takes us on a journey in the life of a prophet; it is a book of deep sorrow, judgement, and ultimately hope. Jeremiah, the prophet, lived during a time of tremendous political chaos and moral decay. Nonetheless, in his over 40 years of prophecy, he never loses a deep love for his people, and his prophecies include messages of hope and restoration. Themes of idolatry, injustice, and rebellion characterize the book of Jeremiah. There is also considerable attention paid to abuse in positions of leadership (including false prophets spreading lies), and times where Jeremiah’s commitment to the truth cost him dearly.

Lamentations

We begin with the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. Babylon has won. The outlook is bleak. The book of Lamentations earns the prophet Jeremiah the epithet, “the weeping prophet.” Jeremiah is one of few prophets who watch their own prophecies unfold and thus, he is undone. Lamentations examines questions of grief, trauma, and survival through a theological lens. Taking questions that are often placated or receive shallow optimism and instead, revealing how faith and sorrow can coexist. How pain doesn’t contradict God’s presence, and ultimately reveals a deeper, more profound picture of who He is.

Ezekiel

Written by a former priest, turned prophet, Ezekial is a book of visions. Arranged around a progression from judgment to hope—and from glory lost to glory restored—Ezekial challenges his people using bizarre demonstrations and symbolism. Ultimately the prophet challenges the view of communal fatalism, insisting that no matter how great their failures, God isn’t finished.

Daniel

More than simply moral tales, the book of Daniel is politically subversive. Written at a time when Israel was in exile and ruled by a nationalistic empire that demanded their worship, the book of Daniel insists that only God reigns supreme. This book also deals in complex apocalyptic visions of the future. These visions require a modern audience to examine the ancient context a bit more closely. Though on the surface it may seem a rather bizarre or foreign book, it holds truths relevant to struggles felt in modern day.

Hosea

The book of Hosea is often misunderstood. Powerfully blending personal drama and national prophecy, this book uses Hosea’s own marriage to an unfaithful wife as a metaphor for God’s relationship with unfaithful Israel. Though Israel’s history is rife with apostasy and rebellion, Hosea showcases a kind of love that is unconditional. A love that intentionally forgives, even when fairness suggests it shouldn’t have to. Theologically, Hosea does not excuse sin, but it demonstrates that because of His perfect love, God’s justice can exist in tandem with his mercy.

Joel

A locust plague becomes a wake-up call in this prophetic book. Though only a few chapters long, the book of Joel is rich with symbolism and graphic in nature. Though a judgement is pronounced, there is also promise of blessing and redemption. There are also many significant references to the coming Messiah and even the Holy Spirit.

Amos

Written at a time of affluence for the kingdom of Isreal, the prophet is not fooled. Amos identifies the moral decay he sees clearly in the Northern Kingdom. He points out how the rich may be thriving, but the poor are being exploited and neglected. He also shows how the rituals and worship of God’s people are meaningless without the presence of justice and righteousness. Amos punctuates his message with the truth that mercy is only possible through repentance; God’s people are responsible for the posture of their hearts.

Obadiah

Family betrayal is the catalyst of the book of Obadiah. This book is personal. Obadiah speaks to the unchecked pride of Edom, and despite their family ties, pronounces judgement for their betrayal of Judah. Obadiah may be the shortest book of the Old Testament, but it is packed with drama and themes of justice, pride, and restoration fill its 21 verses.

Jonah

Perhaps one of the most well-known stories in the Old Testament, Jonah is far more than a fish-tale. Beginning with a rebellious prophet, the biggest miracle in Jonah actually has nothing to do with the whale. In this book, we wrestle with difficult questions regarding forgiveness, compassion, and hatred, forcing us to examine our own ideas of mercy and judgement.

Micah

Social justice is at the heart of this brief book. Though considered one of the minor prophets, Micah will later be quoted by Jeremiah, and his prophecy will be connected to Jesus in the New Testament book of Matthew. Micah emphasizes the need for humility and speaks strongly against hypocrisy and corrupt leadership. Throughout the 7 chapters of Micah, the prophet insists that God’s people must do more than worship—they must embody God’s character through justice and mercy and through humble faithfulness.

Nahum

Assyria, the superpower of the ancient Near East, is known for its barbaric violence and military strength. In the book of Nahum, the prophet boldly prophesies its downfall. Though Nineveh, its capital city, briefly repented with the prophet Jonah, Nahum foretells the destruction of this once again morally bankrupt nation.

Habakkuk

The book of Habakkuk reads less like a prophetic oracle and more like a personal prayer journal. Throughout Habakkuk, the prophet asks many vulnerable questions of God; themes of which include questions of divine timing, doubts in times when God is silent, and why God allows wrongdoing. This conversational approach allows a reader to immerse themselves in a divine dialogue. The depth of which is seen all the more clearly as we examine the cultural and historic backdrop.

Zephaniah

At the time Zephaniah writes this prophetic book, Assyria’s power is waning. However, this is allowing Babylon to rise, and Zephaniah attempts to warn his people. The idolatry the prophet points to extends beyond foreign tribes and he calls out instances of syncretism within Judah. Though divine accountability applies to all, Zephaniah ultimately delivers a message of hope in a time of political and national instability.

Haggai

After 70 years of exile, the Jewish people are finally returning from Babylon under Cyrus the Great (539 BCE) … Though the Israelites initially begin rebuilding the temple, soon opposition and discouragement overwhelm them. For 16 years, the temple lay unfinished while people focused on rebuilding their own homes and businesses. Haggai and Zechariah were raised up to call the people back to their spiritual priorities!

Zechariah

Like Haggai, Zechariah urges the people to rebuild the temple—but he focuses on spiritual restoration as well. He knows that the nation of Israel needs more than a building to regain their belonging. Zechariah will deliver eight powerful visions and become one of the most quoted prophets in the gospels, providing rich symbolism and depicting numerous scenes that ultimately Jesus will fulfill.

Malachi

Malachi opens with the temple now rebuilt. The people are no longer exiled and without a temple, and yet revival had stalled. The Israelites expected more—they were weary and had anticipated more blessings after returning from exile. Worship was half-hearted, priests were corrupt, divorce was common, and social injustice prevailed. Basically, God’s people are simply going through the motions. That’s when the prophet Malachi steps in and challenges this spiritual decline by calling for covenant renewal and authentic devotion.

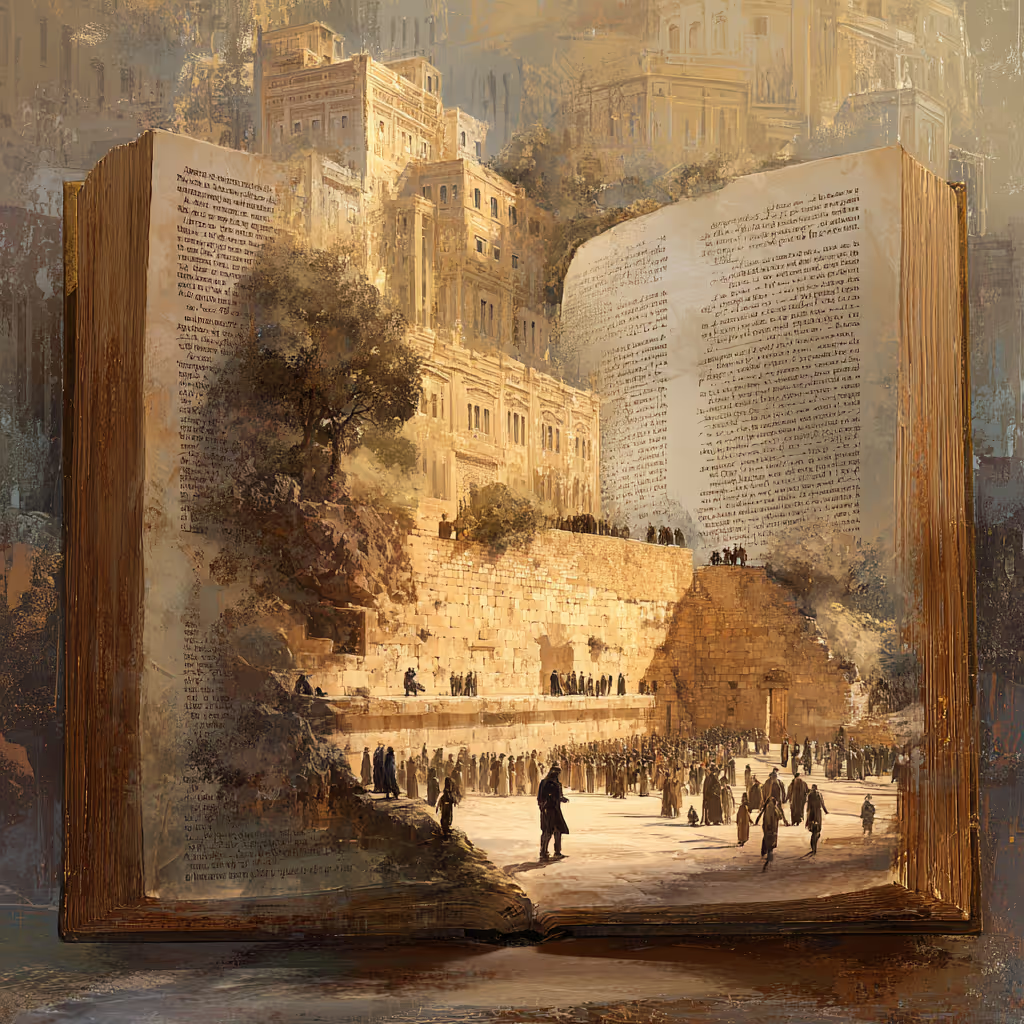

New Testament

The New Testament—or New Covenant—is one of the most profoundly disruptive documents in world history. The birth of Christ marks even the beginning of a new era of time—A.D. Anno Domini. Written in the mid-late first century, the New Testament connects the birth of Christ to the messianic prophesies of the Old Testament, and so much more. As we journey through the accounts of firsthand eyewitnesses, relatives of Jesus and even enemies turned into allies, a story unfolds of epic proportions. Journey into a world full of political tension, superstition, and a world rife with polytheism and cultic ritual. Written amidst the violent rule of the Roman Empire, the threat of death or torture is ever present. In fact, most New Testament authors will be martyred for their faith. It is in this hostile environment, however, that each author produces the theological masterpieces that define Christianity even today.

Matthew

Written by a tax collector, the book of Matthew was written primarily for a Jewish audience. The author beautifully bridges Jewish tradition and the emerging Christian faith, emphasizing Jesus’ fulfillment of the Messianic credentials. One of the three Synoptic Gospels, Matthew provides an extensive genealogy, as well as a thorough account of Jesus’ life and ministry.

Mark

The second of the Synoptic Gospels, the gospel of Mark is attributed to John Mark (called Mark) who is not one of the original 12 disciples. It is a widely held belief that it contains much of the source material for the other two Synoptic Gospels, Matthew and Luke. Mark’s intended audience was primarily Gentile and this gospel book was written during an intense period of persecution of early Christians. His narrative is fast-paced and action packed! And he describes in tremendous detail the suffering Jesus endured in the final week of his earthly life. What Mark offers is a tangible and raw account of the passion Jesus demonstrated, despite the conflict and adversity he faced during the course of his ministry.

Luke

The third of the Synoptic Gospels, Luke’s account deals largely with the marginalized figures of society. In this way, his gospel pairs with the book of Acts as Luke delivers a holistic view of the emerging Christian church. Although Luke was likely a Gentile (and not a member of the original 12 disciples), he writes in such a way as to explain the importance of Jewish traditions and customs as they pertain to the Messiah. His sensitivity to often overlooked members of society showcases a facet of Jesus’ ministry that would prove far more disruptive than any militant action could.

John

With an emphasis on what scholars refer to as “high Christology,” John’s gospel differs from the three Synoptic Gospels in its attention to Jesus as God. This is not to suggest that John’s account contradicts Matthew, Mark, and Luke, but rather that whereas the Synoptics illustrate Jesus’ humanity, John showcases his divinity. In this way, the four gospels give us a fuller understanding of a god who became flesh in order to redeem his creation. John follows Jesus’ life closely, but he highlights seven key miracles in particular, revealing Jesus as divine. John also makes a point of delving deeper into the theological profundity of Christianity—providing reflection for religious leaders (both Christian and Jewish) who were facing tremendous pressure at the time.

Acts

“You will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth…” The book of Acts marks the very beginning of Christian history. Written in a turbulent political climate, amidst the persecution of deranged emperors, the book of Acts chronicles the challenges faced by the earliest Christians as they attempted to navigate what the resurrection truly meant. Themes of the Holy Spirit, what it means to live a holy life, and community with those who come from dramatically different backgrounds fill the pages. As we follow Luke’s narrative, we encounter places such as Akeldama, the Beautiful Gate, and even Herod’s palace where Paul is placed under house arrest. Throughout Paul’s three missionary journeys, we will also examine the world of ancient Rome—full of pagan religious cults, including the cult of Aphrodite, the Delphi Oracle and many others. These will all provide important theological insights that remain relevant even today.

Romans

Authored by Paul, this letter to the Roman church is addressed to a largely Gentile audience. This impacts Paul’s approach, as he frames his explanation of God and righteousness within the context of Greco-Roman cultural practices. Paul navigates the tension that the Jewish-Christians in this congregation would have been feeling carefully and offers a modern reader tremendous insight as to how to properly address internal conflicts and areas of cross-cultural sensitivity. This is not a lighthearted message; themes of greed, pride, and sexual impurity are on Paul’s mind as he writes his Roman brothers and sisters.

1-2 Corinthians

Written approximately a year apart, 1-2 Corinthians chronicle one of Paul’s more challenging relationships with the churches. Though Paul was successful in establishing a church at Corinth, he at times struggled with how to reach the culture of Corinth. 1 and 2 Corinthians form a compelling portrait of a first-century church and what it was like navigating theological confusion, ethical challenges, and the tension that inherently comes with leadership. Paul’s responses are both theologically rich and pastorally sensitive, offering timeless guidance on church unity, spiritual maturity, and the nature of Christian leadership. These letters remain foundational texts for understanding early Christianity and the lived reality of the gospel in community.

Galatians

One of Paul’s harshest letters, Galatians was written as a loving rebuke. Addressed to the churches in Galatia (modern-day Turkey), the letter responds to a crisis: namely that the gospel was being twisted. In fact, Paul himself had come under fire and was being slandered. But Paul’s letter isn’t a defense of himself; he’s writing to defend the truth and clarify for these early believers that faith in Christ alone saves. It challenges both legalism and syncretism and illuminates what an identity in Christ truly means.

Ephesians

Written to the church at Ephesus, the letter itself is far broader in content than any of Paul’s other correspondences. This is likely due to the position of Ephesus as a major trade route—strategically positioned and accessible to people from all over the known world. Rather than addressing specific controversies or crises, Ephesians offers an eloquent vision of God’s eternal plan in Christ, emphasizing unity, spiritual identity, and ethical living in light of the gospel.

Philippians

Written to a proudly Roman town, rich in gold and silver mines, Paul’s letter to the church at Phillipi emphasizes humility and joy amidst suffering. In this letter, Paul will use many distinctly Greek and Roman references to illustrate his message and allude to his almost certain impending death. In this brief book, Paul provides a vision for a life in Christ—one that maintains a fixed gaze on eternal purpose.

Colossians

Authorship of Colossians has been hotly debated. Ironic for a book that deals largely with the false teachings that arose in Colosse. In Colosse, believers were being influenced by teachings that mixed Christian faith with elements of Jewish legalism, Greek philosophy, mysticism, and ascetic practices. Paul (possibly Timothy or other apostle) writes for the purpose of clarification. In this letter, Paul adamantly defends the supremacy of Christ and the finished work on the cross.

1-2 Thessalonians

1-2 Thessalonians may be brief, but these letters have been referenced by early church writers dating all the way back to the second century. Written in approximately 51-52 A.D., Paul is addressing the church at Thessalonica. One thing that Paul is clearly seeking to do in his letters is to encourage the church in Thessalonica, as well as provide further teaching for new believers. Although facing an incredible weight of persecution, they were still faithful and growing. But Paul knows this is only the beginning—he’s very aware of the severe persecution they will inevitably face. He doesn’t shy away from the hardships and trials they will likely endure. In fact, this theme will actually grow in sense of urgency as we move from 1st to 2nd Thessalonians and the persecution the church faces increases. However, Paul makes clear that this opposition is actually all part of God’s plan and he teaches them how to use it to make them stronger.

1-2 Timothy

Timothy presents a unique character in the New Testament—first appearing in the book of Acts. Timothy joins Paul’s mission team early on, and they quickly form a bond. Paul refers to him as a “son” and diligently disciples him. In the books of 1-2 Timothy, we see that he is in need of encouragement, and these letters not only combine personal encouragement, but also pastoral instruction, and warnings against false teaching. No doubt due to the fact that Paul’s own fate was looming close, these letters strike an emotional tone. This is Paul’s final letter, written from prison in Rome, likely under sentence of death. In this deeply personal farewell, Paul urges Timothy to remain faithful, endure suffering, and carry on the gospel mission. He offers a vision for church leadership, sound doctrine, and faithful ministry in the face of both external challenges and internal threats.

Titus

Written by Paul and delivered by Zenas and Apollos, this brief letter is dense with words of wisdom and instruction. Titus was a valued associate of Paul, but he was entrusted with a difficult task, leading the church on the island of Crete. This island was known for moral depravity and finding leaders among them has clearly presented a challenge for Titus. Paul writes, not only to encourage, but also to advise Titus. In his letter, Paul makes many cultural and geographical references that have significant theological implications. A mere 3 chapters long, Paul provides a wealth of insight.

Philemon

Written by Paul, the book of Philemon is uniquely personal. In this letter, Paul is addressing a friend on behalf of a runaway slave. Paul refers to himself as a “slave of Christ” as he urges Philemon to “do what you ought to do.” In a single chapter, Paul paints a picture of a radically different social order, and he undermines the entire system of slavery in only a few short words. Furthermore, Paul depicts a sort of heavenly family dynamic that is devoid of hierarchy or class—instead it is fully submitted to the will of God.

Hebrews

The author of this brief book is unknown. What we do know is that the author was a friend of Timothy’s, spoke fluent Greek and was well educated in the Old Testament. There is a sense of urgency in the author’s tone, likely because at the time Hebrews was written, persecution was a very serious concern. Like the author, the audience of Hebrews has also been debated. Most likely written to Hellenic Jews, the title of “Hebrews” was not part of the original text. The author stresses the importance of the New Covenant and the superiority of Christ and pays attention to compromises being made in both Jewish-Christian and Gentile-Christian environments.

James

Addressed to the “twelve tribes,” most attribute the book of James to Jesus’ brother. The inclusion of all twelve tribes is significant for this moment in history, and the author bears an especial burden that the earliest disciples openly shared. This letter is strongly worded, containing many exhortations to live a moral and upright life. James does not hold back—he makes clear that as believers, we are called to a higher standard.

1-2 Peter

The authorship of 1-2 Peter has been a source of much debate—largely due to the fact that Peter is elsewhere referred to as “simple” or “unschooled.” But these arguments ignore the more likely implication that Peter was simply not “college educated.” He was, however, a businessman (fisherman by trade) which would have required literacy and a knowledge of Greek. Furthermore, Peter specifically mentions that he enlisted the assistance of Silas in writing the letters. Much of 1-2 Peter has been taken out of context in modern times and thus, caused confusion and at times, division. Written to scattered believers in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), these letters address Christians living as exiles in a hostile world and offers practical advice for remaining unpolluted by society. While 1 Peter focuses on encouragement amid suffering, 2 Peter warns against false teachers and urges believers to remain faithful as they await the return of Christ.

1-2-3 John

The three Johannine Epistles (1 John, 2 John, and 3 John) are traditionally attributed to John the Apostle, the “beloved disciple,” who also authored the Gospel of John. These letters reflect the theology and style of the Fourth Gospel and are deeply concerned with truth, love, obedience, and fellowship with God through Jesus Christ. While 1 John reads more like a theological sermon or pastoral tract, 2 and 3 John are brief, personal letters written to specific individuals or communities. Together, they address issues of false teaching, Christian identity, love, and church relationships in the late 1st century.

Jude

Full of Old Testament allusions and Jewish apocalyptic imagery, The Epistle of Jude is a short but powerful letter. Written to warn believers against false teachers who had infiltrated the church, Jude urges the faithful to “contend for the faith” and remain steadfast in truth, holiness, and love. A mere 25 verses long, Jude overflows with exhortation and encouragement for a church facing opposition on all sides.

Revelation

One of the most literarily complex books ever written, scholars are still puzzling over the depth of meaning packed into these 22 chapters. Written from exile on the island of Patmos, John records heavenly visions and apocalyptic messages for the seven churches of Asia Minor. These churches were facing levels of persecution that suggested the end times to be near and John’s words no doubt provided strength and encouragement. The Book of Revelation offers a climactic vision of God's ultimate victory over evil, calling the church to faithfulness, courage, and hope. While its symbolic language can be challenging, its central message is clear: God is still in control, His presence is eternal, and He is coming back.